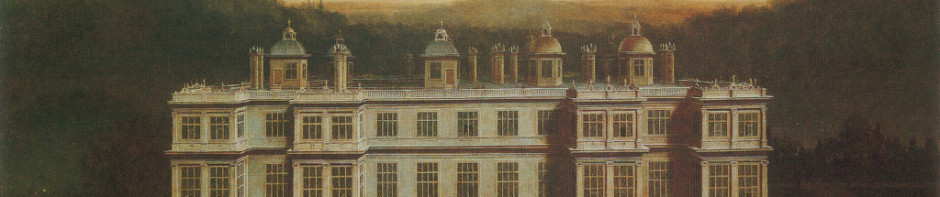

Inspired by a recent cnn.com article about how to fund a British stately home or manor house in modern times, I thought I would write about how my three favorite houses have handled this. For Wollaton, see here. Next up: Longleat

Longleat was built by the ambitious Sir John Thynne. He began converting an existing priory in 1540 and did not stop tinkering with the building until his death in 1580. The building that stands today is actually considered the fourth Longleat, replacing an earlier building that caught fire in April of 1567. In 1568, a stonemason named Robert Smythson joined the workforce at Longleat and, although probably not responsible for the final design of the building, he learned all the skills and vision he would need to continue his career at Wollaton, Hardwick, and other locations.

The story of Sir John Thynne and the building of Longleat is a story in itself, and one that I am hoping to tell in fictional form. For now, let’s concern ourselves with the current state of Longleat and how it affords to maintain itself. Longleat has been continuously owned by the Thynne family since its construction and almost continuously occupied by the family.

The Thynne family has been successful; the original Sir John rising from a steward of Lord Protector Edward Seymour, 1st Duke Somerset, and surviving Somerset’s disgrace and eventual execution for treason. Throughout the following generations, the family has risen with a succession of titles, first the 1st Baronet of Kempsford, quickly followed by 1st Viscount Weymouth, to Marquess of Bath.

Currently, Longleat is home to Alexander, 7th Marquess of Bath, his son Ceawlin, current Viscount Weymouth, and grandson John. In the last few generations, the family has taken steps to ensure there will be Thynne’s at Longleat for years to come.

In 1946, Henry Thynne became the 6th Marquess of Bath, inheriting the Longleat estate along with £700,000 death duties or inheritance taxes. Over the next few years he struggled to maintain the house and estate which cost more to run than it earned. He decided to fix up the house and then open it to the public. In April 1949, Longleat became the first privately-owned stately home to admit the public on a regular basis. Rooms were converted to a gift shop and café, and members of the family acted as tour guides and parking attendants. By the end of the first year, over 135,000 people had paid to visit the house.

Later, the animals were added. In the mid 1960s, the 6th Marquess of Bath began conversations with an animal trainer named Jimmy Chipperfield. In 1966, the Safari Park at Longleat opened, which has grown and increased over the past fifty years. Longleat is now a popular tourist destination complete with train and boat rides, multiple animal exhibits, one of the largest hedge mazes in the world, and many other attractions.

The Lions of Longleat

Interestingly, Sir John’s family crest includes a red lion with a knot in his tail. Sir John was knighted on September 10, 1547, following the Battle of Pinkie, by Edward Seymour, Duke of Somerset. The lion is the symbol of Scotland, whom the English defeated in the Battle of Pinkie, and Sir John adopted the symbol of a defeated lion for his crest. So, lions have long been associated with the Thynnes of Longleat.

I think the original Sir John Thynne would have approved of these changes. Surprised certainly, but I think he would have approved. Above all else, Sir John was a survivor and a man who would do what was required to keep his house. That his descendants have found a way for Longleat to not only survive, but thrive, I think would have pleased him.

Longleat's hedge maze

If you find yourself in Wiltshire, take some time to visit Longleat. Whether you lose yourself in the maze, watching the lemurs, or touring the house itself, you will enjoy yourself. I know I did.

Some of Longleat's current residents

References:

Thynne family tree https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Template:Thynne_family_tree

Longleat: The Story of an English Country House, by David Burnett, 2009 The Dovecote Press